By Mansoureh Hosseini Yeganeh

At the time when I was born, the veil was not yet compulsory in Iran. However, I was raised in a religious and traditional family that observed hijab even before the 1979 revolution.

Until my teenage years, I never saw a woman without a headscarf, except during women’s meetings or gatherings with the immediate family. I thought the world had always been like this and that all women dressed in dark colours, kept colours and beauty behind closed doors, away from male strangers.

In the society in which I reached womanhood, my body was never appreciated, and I was always ashamed of exposing my body. Now that I have distanced myself from that society for many years and I no longer wear hijab, I sometimes feel ashamed of my body and I ask myself, “Is it really possible to wear this dress without feeling shame and guilt?”

This is a narrative and a message from a land in which those who were born some 40 years ago never saw women in the streets dressed in clothes they freely chose to wear. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that women in Iran have never been seen as liberated.

Women: The First Victims

The last thing the revolutionaries of February 1979 thought about was the issue of women's clothing after the establishment of a religious government.

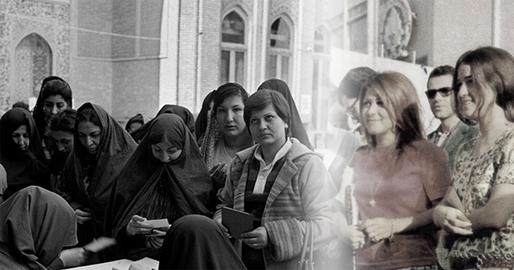

During the reign of the first Pahlavi monarch, women were at one stage forcefully compelled to remove their hijab, though later, the last shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, never involved himself with the hijab issue. At the time, Iran was going through a period when everyone in society dressed in whatever fashion they choose, and women didn’t imagine they would become the first victims of a theocracy that emerged with the advent of the Islamic Republic.

Many unveiled women attended the demonstrations and gatherings against Reza Pahlavi. And some stories even suggest that the Radio and Television’s female employees who wanted to participate in these gatherings went to hairdressers beforehand to look well-groomed at these meetings. But gradually, appearing without hijab became very rare and then stopped altogether.

Women were instead advised to "temporarily" wear some form of head covering to engage in a show of unity. Later, men and women took part in separate marches.

At that time, no one forced women to wear hijab! Some women thought that displaying a unified appearance on a temporary basis might help attain the goals of the demonstrators much faster.

And when the newspapers published photos of women of the royal family in swimsuits on the seaside, the same women who did not believe in hijab but were wearing it to achieve their political goals quickly hid their family photo albums, fearing that the pictures might fall into the hands of the revolutionaries. Little by little, it become evident that hijab was no longer just a piece of cloth that would be worn temporarily and taken off at will.

Harassment and Uncertainty on the Eve of the Revolution

Documented accounts reveal that even before the shah left the country and the regime was changed, all the way back to the fall of 1978, women without hijab were harassed and subjected to knife and acid attacks that the National Organization of Academics condemned in a statement in November 1978.

Ruhollah Khomeini, the founding father of the Islamic Republic, also reacted and demanded an end to such outrageous behaviours. In an interview with Al-Safir newspaper published in Beirut on November 19, 1978, he spoke about the equal rights of men and women in Islam. He emphasized that women had "the freedom to choose or to be chosen, the freedom to educate themselves while working and engaging in any kind of economic activity.”

Khomeini made no mention of the right to freedom of dress, and it seems that by emphasizing the women’s "right to self-determination" he was referring to their freedom to participate in demonstrations and elections.

It seems that, at that juncture, those issues were mostly mentioned so that half of the potential force that could be used for securing the victory of the revolution did not become passive or alienated due to fear of losing some of their freedoms and privileges.

Years earlier, Khomeini was against women’s right to vote and wrote a letter to the shah highlighting the concerns of religious scholars (Ulema) and Muslims on this matter. However, in the middle of the revolution, he did not express any reservation regarding the rights and freedom of all women to vote.

What Khomeini said about the hijab prior to February 1979 was quite limited and vague and without any direct reference to dress code or other issues related to women’s rights.

In perhaps his clearest remarks about hijab, Khomeini said on December, 28, 1978, that no one was forced to wear a chador. But he did not make it clear if women were to be free to dress as they pleased. But, by saying that "we will only ban ‘skimpy’ clothes," he was giving a free hand to decision-makers to decide what constituted appropriate clothing for women.

At that point, many men and women began to feel the forebodings of serious concern and danger. Gross generalization about the status of women was perhaps one of the main reasons why protesters during a mass demonstration held on January 25, 1979, reverted to the slogan "The king should reign and not rule" demanding a return to the provisions of the 1906 constitution.

According to press reports, some 150,000 people participated in those demonstrations in which three-fifths of the participants were women. But those rallies were subjected to “stone-throwing” by Islamic revolutionary elements anxious to swing matters in favour of Khomeini before being dispersed. That rally can be seen as the very last attempt by women to save their rights before the victory of the 1979 revolution.

Even after returning to Iran, Khomeini continued to speak in vague generalities about women’s rights, but the threat became more palpable a week prior to the victory of the revolution when Ayatollah [Mohammad Kazem] Shariatmadari (another leading cleric) made comments regarding “strictures that restrict women in Islam” (Ghezavat Zanan).

Islamic laws against women soon became clearer and instilled fear into the hearts of many. But the revolution was now on its way to victory, and it was no longer possible to stand in its way.

The Coldest Winter for Women

Once the joy and excitement that immediately accompanied the revolution’s victory started to subside, even before the referendum calling for the creation of an Islamic Republic was held, the revolutionaries decided to launch the process of Islamizing the country, starting with women.

On March 7, 1979, on the eve of that year’s International Women's Day, Khomeini ordered women to observe hijab in offices. The next morning, those who did not wear a headscarf were not allowed to enter their workplaces and were told to go back home and get one.

But many women refused to return home and instead went to the streets to hold the first march against mandatory hijab in a protest movement that continued for three days. Meanwhile, Ayatollah Mahmoud Taleghani (a prominent figure of the 1979 revolution) said that hijab was not mandatory and that “wearing a piece of cloth should not upset anyone.” A cursory glance of documents, speeches and statements from those key days show that an effort was made to calm the protesting women through mediation and “wise elderly advice.”

Despite all this, Khomeini maintained his previously stated position that wearing the chador was not compulsory, but he now inserted a proviso requiring women to cover themselves. His son-in-law, Ayatollah Eshraghi, was blunter when he said that Khomeini's “wish was that the Islamic hijab had to be implemented and, therefore, women were required to observe the hijab."

Various documented records show that women reacted by resorting to every possible action in their power, from sit-ins and protests against the lack of media coverage, especially state radio and television, of their demonstrations against mandatory hijab, to speeches, interviews and mass gatherings in universities.

In the face of such acts of defiance, Khomeini no longer made any direct comments on hijab and even supported remarks made by Ayatollah Taleghani and others about the headscarf not being mandatory.

From Gradual Downgrading to the Coup de Grace

From March 1979 to July 1981, Khomeini made no additional comments regarding hijab. But during this period, women were barred from attending all public sporting events, while the new education authorities accelerated the dismissal of women teachers for allegedly giving the opportunity for free and open discussions in class. Also, women were banned from being judges, gender segregation was applied on beaches and strict guidelines regarding the type of clothing suitable for female athletes were introduced.

The only achievement for protesting women was that female nurses and care-givers should continue to work wearing their short-sleeved white uniform with its distinctive hat.

Later, on the order of the Revolutionary Committees and with the specific aim to separate men and women, the swimming pool of the Ararat Club, which belonged to the Iranian Armenian community, was closed. Similar strictures continued to be imposed well into July 1979, after which more forceful measures began to be implemented regarding compulsory hijab and other issues related to women’s presence in society.

Media reports soon emerged that women were banned from serving in the armed forces and from entering their workplaces without hijab. It was also reported that merchants in Shiraz Bazaar demanded that shoppers without hijab should be prevented from entering the market.

As revolutionary forces called for enforcement of increasingly draconian measures, women returned to the streets, with the Tehran daily newspaper Kayhan contemptuously calling the demonstrators "a bunch of prostitutes and dishonourable people."

While these last efforts ultimately failed to achieve anything, their coverage in the media became a shameful vehicle for smearing all the women who had stood up and protested.

On July 1, 1980, Khomeini administered the coup de grâce to women’s right to dress as they pleased by ordering all administrative offices to fully abide to Islamic laws. The move was followed by a presidential decree issued by Abolhassan Bani-Sadr stating that all women working in government offices are required to “observe all Islamic norms in the workplace, including the dress code.” Bani-Sadr warned that in the event of any violation, all women would then be prevented from entering the workplace. He added that persistent violation of this administrative order would lead to all violators being prosecuted and punished.

Consequently, starting from the morning of July 5, 1980, women without hijab were banned from entering government offices, a prohibition that was later (1982) legally codified and subsequently enshrined into law.

In 1984, when I was five years old, the Islamic Consultative Majles ratified the new Islamic Penal Code under which women who failed to wear hijab in public spaces would be sentenced to 72 lashes. The law ha continued in place from the time when I reached the legal age, which made the observance of hijab compulsory for me, until this very day.

For the past 44 years, women in Iran have struggled to the best of their abilities not to submit to these acts of gross intimidation and persecution. In the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, women began to use colourful scarves, while fashion and style was introduced in their mantos, the overcoats they generally wore as part of the dress code. In all these years, women resorted to various acts of defiance by manipulating the size of their coats, pants, scarves and shawls in line with their own tastes.

Meanwhile, widespread protests against compulsory hijab have been a constant feature of Iranian society.

High profile protests against hijab included the self-immolation of Homa Darabi, Parvaneh Forohar’s refusal to be photographed with a headscarf during her interviews and Vida Mohd’s decision to stand up in a crowded Tehran street holding her headscarf on a stick.

Women have replaced their coloured scarves and fancy dresses with black veils and long coats hurriedly pulled out of their handbags before entering their workplaces in government offices – only to replace them once the working day was over. To this day, Iranian women have placed their very lives on the line and never relented in the fight to regain their usurped rights.

For the daughter I don't have

I remember one day when I was 13 years old, I had to wear a headscarf in the August heat while my sister's son, who was three years younger than me, could walk around in a T-shirt and shorts. I remember asking my mother if I could become a Christian in the summer and a Muslim again when the weather once again cooled down? This was not to be. But that day I remember wishing to never have a daughter so she wouldn't have to endure all the heat and discomfort I had suffered from.

Later, discovered that I wouldn’t be given custody for my own child, and I would myself require permission from a “guardian” before leaving the country. Having found out that I would get a lower share of family inheritance, I attributed all these discriminations to the fact that I was born a girl.

It took some time before I realized that being a second-class citizen was a result of having been born on a land that was experiencing a historical precipice in which women were being increasingly marginalized and cast aside.

This was a land in which Bahman (“Avalanche” in Persian) was not just the name of a calendar month in which a revolution came to fruition. Like in an avalanche, women were thrown into a mixture of snow and ice that brought nothing short of a lasting dark winter instead of a promising spring that has never come.

Mansoureh Hosseini Yeganeh, is a London-based Iranian journalist and political activist.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments