Nava Anvari, 29 years old, was born into an Iranian-American Baha’i family in the United States. But in 1994, shortly before the death of her father, Houshmand, and when Nava was just aged five, her family moved to South Africa —giving her an African identity too.

Today, Nava works across the continent for an impact investment fund, while her mother and sister still live in South Africa.

“My dad had been passionate about moving to Africa since he was a youth in Iran,” Nava says, “and he left relatively soon after the Revolution.” South Africa had been living under Apartheid for decades by the time Houshmand Anvari first traveled to the country. He wanted to help develop the Baha’i community in South Africa and to serve Africans in the poor townships.

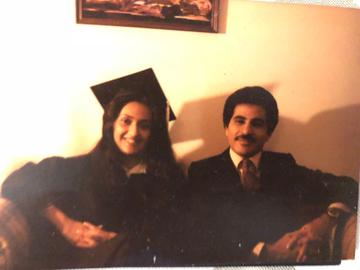

Houshmand visited South Africa before his wife, Dina, also from Iran, agreed to move. Nava says he took hundreds of photos to show his wife that “South Africa had roads ... and that they wouldn’t have to live in a mud hut.”

Dina eventually committed to the idea. She even insisted that the family live in one of the neighborhoods where they could best serve black Africans who were segregated from the rest of society because of Apartheid. The family settled in East London in the Eastern Cape, and from 1990 they began spending their weekends in the nearby black township of Mdantsane. The township was one of South Africa’s poorest, and it was a radical act for a non-black family to visit the community.

Houshmand spent part of each weekend building a small school in the garden of the Baha’i Center in Mdantsane. “I remember that it had colorful chairs inside it,” Nava says, “and there was a roof that was being painted. I have only one memory of being inside that room with a bunch of children, doing a children’s class with my dad.”

Blacks this Side, Boers that Side

March 13, 1994, was a Sunday, and Houshmand was visiting Mdantsane to continue work on the school. The rest of his family had remained home in East London. Dina was feeling unwell, so Nava, her sister Ava and her brother Vafa also stayed behind. A black South African friend of the family, Tami, was with Houshmand, and later told Nava and her family what happened that day in Mdantsane.

“It was the international day of the family,” Nava says, “And they were having workshops [at the Baha’i Center] on family planning ... there was a group of Baha’is, including a number of children. But they were all black children. There were only three Iranians or non-blacks there – my dad, his friend Riaz Razavi and another Baha’i named Shamam Bakhshandegi.”

Tami and the others were waiting for Houshmand inside the Baha’i Center – he was working on the roof of the school. Tami explained to Nava that her father then “walked into the Baha’i Center, with his hands up, but he was dancing and smiling and making faces.” And then Tami saw five men with machine guns walk in behind Houshmand.

The men were black South Africans and they claimed to be soldiers acting under orders from the Azanian People’s Liberation Army – or APLA – which was the military wing of a group that had broken away from Nelson Mandela’s anti-Apartheid party, the African National Congress. The militants’ motto was “One Boer, One Bullet,” referring to the Dutch-descended and landowning Boer ruling class of Apartheid South Africa, and the APLA’s policy of violent retribution against Boers.

South Africa was in turmoil in its last days of Apartheid in the early 1990s, and militants like APLA used the instability and uncertainty to vent a brutal fury created both by decades of racial injustice and by populist politics.

The APLA gunmen behind Houshmand tried to separate the people grouped inside the Baha’i Center. They ordered the “blacks this side,” and the “Boers this side.” Houshmand hesitated – thinking perhaps that Iranians would not be considered to be Boers – but he and the other two Iranians were moved to one side of the room.

Nava recalls: “It was very foreign to the Baha’is to separate racially” because of the religion’s teachings on the oneness of the races. The Anvaris had never felt white, black, nor “colored” in the South African sense; they were Iranians who were choosing to stand and live alongside black Africans.

But the gunman saw the Iranians as “Boers” because their own perspective had been forced into a distorted shape by decades of Apartheid. They insisted that “there is no space in the new South Africa for the white man,” Nava says. And they gunned down her father and the other two Iranian men. Houshmand died on the spot.

“My dad was smiling until the last moment,” Nava says, drawing from her friend Tami’s testimony. “[He was] pulling faces because he didn’t want the children to be scared. He never looked afraid, he never looked sad, he never looked desperate. His last thought was how to protect those children from something traumatic.”

African by Choice

When Thabo Mbeki, president of South Africa from 1999 to 2008, pardoned one of the gunmen sometime around 2002, it angered and frustrated Nava.

“My mother kept trying to empathize with the guy when he was let out of prison,” Nava says, remembering that the gunman had killed her father when he himself was just 18 years old and had a two-year-old child. Nava saw that it was her mother’s commitment to ideals of forgiveness and compassion that made it possible.

“I lost my dad because of angry people,” she says, “and purely out of that hate and anger and desire for revenge. It’s irrevocably changed my life. If I continue to hold on to that anger, how many other lives will it destroy?”

Nava also did not abandon her African identity – not that she had any other option.

“My identity as an African was developed over many years of my mom refusing to allow us to distinguish ourselves from the rest of the African kids,” Nava says.

“Our summer camps would be at the Baha’i Center, where we were one of five Iranians in 40 [African] people,” she adds. “And we were never given the opportunity or the space to set ourselves apart. My identity was merged with my dad’s the moment his blood was shed. Anything I did for personal gain, and for personal pleasure, that took me away from South Africa, would feel like I’m betraying what he gave his life to do.”

Nava may think her African side was the product of circumstance and tragedy – but to me it seems like she made the right choice.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments