On the last Friday of the fourteenth Iranian century, on March 19, 2021, an old Iranian man died in Berlin. The passing of this elderly man went largely unnoticed, but marked the end of an era in leftist politics in Iran.

Ali Khavari had led the Tudeh Party of Iran since 1983, and died in exile just two days before his 98th birthday. In the aftermath, the Tudeh Party issued a statement addressing "members, supporters, friends of the party, the working classes and toiling laborers", in which it declared: “Until the last moments of his prolific life and despite his illness, he did not resign from his post. He had always said that as a party soldier he would not fail, and in one of the most difficult and sensitive periods in our party’s history, he played a special and definitive role in the continuation of the work and struggle of the Tudeh Party of Iran."

In its statement, the Tudeh Party also recalled an article by Rahman Hatefi (pen name Haidar Mehregan, an Iranian journalist who died in custody in 1983) published in February 1978 in the then-Tudeh Party underground newspaper, Navid.

In this article, Hatefi had called called Khavari, who had by then spent more than 14 years in prison, "the voice of our party's legitimacy". He wrote of Khavari: "Comrade Khavari is not just a prisoner. He is one of the spiritual assets of our militant proletariat."

For his part, throughout his years in exile, Khavari never forgot the days when his party really was a Tudeh, or mass, rather than the scattered and disparate group it became. The Fadaiyan-e Khalq (the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas, a Marxist-Leninist movement) has also issued a statement after his death, acknowledging Khavari’s "prominent role" in the development of the Tudeh Party over the past four decades, adding that it "deeply respects his memorable stand in the struggle for justice in Iran and praises his resilience in prison".

From Mashhad to Berlin

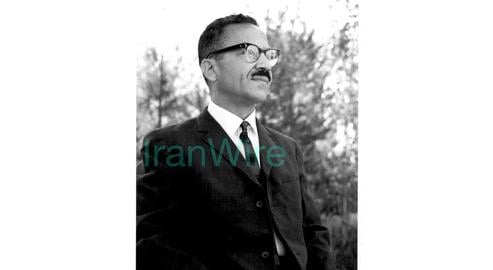

Khavari was born on the first day of Farvardin 1302 (March 22, 1923) in Mashhad, which was still considered part of the Guarded Domains of Persia under the Qajar dynasty. His father, Adib Khavari, was a poet and reciter of poetry in Arabic and Persian, and their house was a regular hub for readings and events.

His brother, Abdolrasoul Khavari, was an activist and cadre of the Communist Party of Iran, a group which was itself part of the Communist International (Comintern) organization. Its leader, Avetis Sultanzadeh, is famous for having gone head-to-head with Vladimir Lenin at the Second Comintern Congress.

The Communist Party of Iran, however, was dispersed by the repression of Reza Shah and the purges of Joseph Stalin. In 1941, when the Tudeh Party was formed, 18-year-old Ali was influenced by his brother’s leftist ideas. His brother became a member of the Tudeh Party’s Khorasan Provincial Committee, and Ali quickly became active in the party's youth organization in Mashhad, formally joining the party in 1943. One of the first party figures who met and established ties with him was Mohammad Boghrati, famously one of “The Fifty-Three”: a group of 53 Iranians arrested and sensationally brought to trial under Reza Shah Pahlavi.

Khavari was among those who had already left Iran before the coup d'état of August 19, 1953, when clampdowns on the Tudeh Party intensified. The party had sent him along with several others, including the Tudeh Colonels Navaei and Chalipa, to Beijing, the new capital of the People's Republic of China, which had been established in October 1949 under the leadership of Mao Zedong.

Tudeh Party members in China had been tasked with teaching Persian at the University of Beijing, and with running the Persian programming of Beijing Radio. Khavari later said that going to China was "an interesting grounding in how a state with so many people had struggled to get out of poverty and deprivation and to build a new country."

In the period after Stalin's death in 1953, however, the Soviet Union, led by Khrushchev, clashed with Maoist China, and the Tudeh Party ultimately sided with Moscow. "It was difficult to stay there, because the differences escalated and because we opposed the Chinese Communist Party's position," Khavari said. "Of course, I should point out that our comrades in the Chinese Communist Party did not ask us to leave; it was our own wish to go."

Several Tudeh party leaders later became Maoists and were helped to escape from East Berlin by the Maoist youth of the Revolutionary Organization. The Persian program on Radio Beijing was then operated by Maoist youths such as Mehdi Khanbaba Tehrani.

The next mission for Khavari, however, was much harder than Beijing had been. He was called back to Iran with several others, including Parviz Hekmatjoo, Colonel Razmi, and Engineer Masoumzadeh, to organize party forces to resist escalating crackdowns by the Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi government.

The Tudeh Party, however, fell into the trap of intelligence service Savak’s influential mole in the party, Abbas Shahriari: a spy known as the Man of a Thousand Faces. Before being exposed (and later killed by the Fadaiyan-e Khalq), Shahriari saw many leading Tudeh figures and other leftists arrested, Khavari and Hekmatjoo among them.

Both were imprisoned in 1963. Their defense statement in court, which was allegedly smuggled out by the activist and Fadaiyan co-founder Bijan Jazani, offered words of encouragement to those members of the party who were still active. Khavari was sentenced to death, but his sentence was never carried out, while Hekmatjoo was tortured to death in 1974. While in prison Khavari was elected in absentia to the party's Central Committee.

Both Kavari's perseverance, and the fact that his party’s approach was different to that of the Fadaiyan, are evident in the defense submission. Khavari told the court: "The Tudeh Party of Iran has put the defense of the independence and territorial integrity of the homeland, and deep and revolutionary social, economic, cultural, and health reforms, at the top of its agenda, and believes the only way to grow is adhering to a non-capitalist development model that can solve our social problems... The Tudeh Party of Iran, according to its philosophical, political, and social beliefs, opposes the methods of Blanquism, terrorism and any type of Machiavellianism."

It is evident that the Tudeh Party was opposed to both the Shah's tyranny and the notion of armed struggle. Nowhere in his career did Khavari speak of wanting to overthrow the monarchy. When the Shah launched the White Revolution in the same period, many Tudeh Party theorists were positive about it, especially after the Shah established diplomatic and trade relations with the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc.

While in prison, Khavari became acquainted with many of the figures who later rose to prominence in the Islamic Republic. He later recalled that he had accompanied Ayatollah Montazeri and Dr. Habibollah Peyman during the "hot days of the summer of 1966 in Ghezel Ghaleh Prison". Montazeri would later lose his deputy leadership after protesting against the massacres of the summer of 1988, in which many members of the Tudeh party were killed. Khavari also had good relations with Ayatollah Taleghani in the Shah's prison, while he later recalled that figures such as Assadollah Lajevardi, who would go on to become the head of Evin Prison and a torturer of dissidents, "had a strange grudge against the party and the communists, and considered them impure".

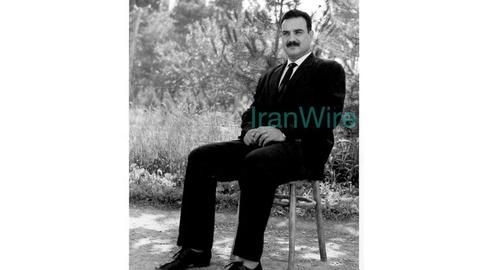

As the Islamic Revolution approached, political prisoners were being released and party leaders were returning to Iran, Khavari was one of the first to be commissioned to begin the Tudeh Party’s public-facing work inside the country. He set up the party's famous offices on 16 Azar Street and published the first issue of People's Letter in the spring of 1979.

In the 17th plenum of the party, which was held in April 1981 at Farhad Asemi's house in Tehran, Khavari was elected to the political board and formally became a member of the secretariat of the Central Committee.

Khavari later claimed that, along with some other party figures, he had opposed then-Secretary General Noureddine Kianuri’s line in defense of Khomeini from the beginning. According to him, this opposition could be implicitly seen in the party's statement condemning the Islamic Republic's attack on Kurdistan on August 19, 1979. Others, however, are sceptical about this, saying there was no indication of Khavari’s going against the Tudeh Party line during his years at top-level meetings, in countries such as Bulgaria and East Germany in 1982 and 1983.

In his memoirs, Khavari also recalls having met with Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani, then-head of the Interior Ministry. According to Khavari, Rafsanjani told him: "Our country needs a leftist party that believes in the revolution, and we think the Tudeh Party is defending the revolution well." However, he says that when he reported his "long" conversation with Rafsanjani to the party's political delegation, he told them he saw the “snake’s eye” in the gaze of this cleric close to Khomeini. He says he was refuted by Kianuri, who told him he was being “idealistic”.

How did Khavari Become Leader of the Party?

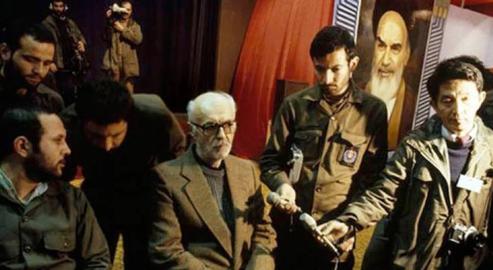

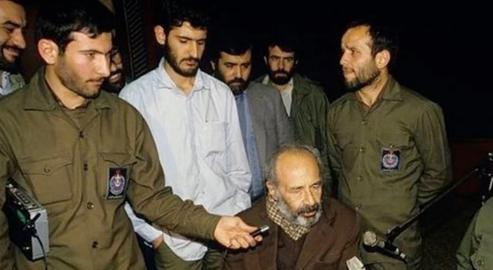

Khavari becoming the leader of the Tudeh Party is a direct consequence of the imprisonment of other leaders of the Tudeh Party of Iran. In the first years after the foundation of the Islamic Republic, the Tudeh Party had officially defended the "Imam's Line" and the leadership of Ruhollah Khomeini. But in February and May 1983, the Revolutionary Guards initiated two waves of mass arrests of party members inside the country.

Tudeh Party leaders were tortured, made to give televised confessions and announce the party's dissolution to the public. The only secretary of the Central Committee who was abroad at the time of the attack was Ali Khavari. In the early years after the revolution, he had traveled to Prague to represent the Tudeh Party in the office of Peace and Socialism, a magazine published in various languages in which many communist parties had a representative.

In his last interview with the Tudeh Party newspaper a few short months ago, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of Iran, Khavari said that when Noureddine Kianuri, the then-Secretary General of the Tudeh Party, wanted to send him abroad, he had "strongly opposed" the idea but eventually relented, considering himself "obliged to implement the decision of the party's leadership". Again, others have disputed this.

Whatever the truth of the matter, Khavari first became the head of the party's overseas committee and then organized its 18th Plenum in December 1983 in Bratislava to rebuild the party. From there he became the first secretary of the reconstructed Tudeh Party in exile.

In recent years, the Tudeh Party has dropped the title of First Secretary; the old Khavari received the title of "Head", which he carried for the rest of his life; his nephew, Mohammad Omidvar, spoke on behalf of the Central Committee on behalf of the party.

At the critical moment of 1983, however, Khavari faced many difficulties in rebuilding the party overseas. Many key figures were critical of Kianuri's posturing in defense of Khomeini and the Islamic Republic, which in the end had not saved the party. In the middle of the Islamic Revolution, Kianuri had suddenly taken over leadership from the previous Secretary General, Iraj Eskandari, and was considered chiefly responsible for the policy of defending the "Imam's Line".

In the very first days of his return to Iran after thirty years of exile, Eskandari, in an interview with the weekly Tehran Mosavar with Faraj Sarkohi, criticized Tudeh Party’s public stance and Kianuri's defense of Khomeini. This, he said, was the reason why the party leadership had sent him abroad.

In the 18th Plenum, therefore, on the one hand, Khavari was faced with an older and anguished Eskandari, who together with younger activists such as Babak Amir Khosravi wanted to see major changes in the party. Some in this faction called for the expulsion of Kianuri and other party leaders. On the other hand, some members robustly defended Kianuri's line, saying the party still ought to defend the "Imam's Line." Beyond this, issues of the party's relationship with the Soviet Union and the theoretical issues of Marxism-Leninism were also disputed internally.

Khavari came to a decision. Kianuri and others were not expelled, but the Tudeh Party took a bold new stance in opposition to the Islamic Republic. Khavari also maintained close ties with the Eastern Bloc countries and adherents of traditional Marxism-Leninism. One of the first actions of the Tudeh Party in exile was to help rescue party members from inside Iran, by helping them migrate to different countries. Some fled to Soviet Azerbaijan, where many leaders of the Azerbaijan Democratic Party had never left Baku for Tehran and still had a strong base. Others fled from the western borders of the country with the help of the Iraqi Communist Party network.

During these years, Khavari was constantly moving between different cities where the Iranian communists had set up bases, from Minsk to Tashkent. Most important, however, was the help of Iran's eastern neighbor, Afghanistan, which now had a communist, pro-Soviet government in place, and whose Persian-speaking leaders had followed the Tudeh Party's history for many years and read its publications. Khavari established close ties with the communist regime in Kabul and in 1985 held a meeting called the "National Conference of the Tudeh Party" in Afghanistan, which was attended by Tudeh cadres from around the world. Some of the party's most prominent figures settled in Kabul during those years, from the poet Siavash Kasraei to Rahim Namvar, an Iranian Jewish writer who died in Kabul and was buried in the city's Martyrs' Cemetery.

The cooperation between the Tudeh Party and the Communist Government of Afghanistan was, of course, to the benefit of both parties. The Iranian communists were mostly highly educated and assisted the fledgling Afghan government in areas such as medicine and mass media. Many of them began teaching at Kabul University, which in those years was known for its advanced education and the unprecedented presence of female students.

In 1984 Afghanistan became the base for Radio Zahmatkeshan, which was housed in a vast mansion with two buildings and a large garden near the German embassy in Kabul, and was the joint tribune for the Tudeh Party and the Fadaiyan-e Khalq’s majority faction, led by Farrokh Negahdar. Kasraei and Rahim Namvar also worked for the radio station. Prior to the revolution, the Tudeh Party had lost its Peyk-e Iran radio station following the establishment of a link between the Shah and the communist government of Bulgaria. But now, during the period known as the Second Migration, it had found a new platform.

Ali Khodaei, who was close to Khavari in Afghanistan in those days, recounts his meetings with Khavari and communist Afghan leaders such as Babrak Karmal and Sultan Ali Keshtmand, the then-Afghan president and prime minister respectively. "Comrade Carmel spoke of the open doors of Afghanistan to our party, and said we would have all the facilities we needed," Khodaei writes.

Khodaei, who is now the lead author of Rah-e Tudeh and has become opposed to the leadership of the Tudeh Party and Khavari in recent years, writes: "Comrade Khavari gives a very good emotional speech. His political and analytical speeches may not be as interesting, but he is exemplary in the area of arousing the audience's emotions, especially since he always has proverbs and short stories and poems in his arsenal."

According to him, the leaders of Afghanistan cried after Khavari spoke about the suffering, imprisonment and suppression of members of the Tudeh Party. "Especially when he spoke of the torture inflicted on Ehsan Tabari,” Khodaei writes, “and how he was punched in the mouth by a military man in prison so that he would remain silent and not speak."

The Afghan communists generally read and were familiar with Ehsan Tabari’s books. While under torture, Tabari had written a book called Deviation, criticizing the history of the Tudeh Party and saying that he had converted to Islam and abandoned Marxism.

These years coincided with seismic changes within the international communist movement, which would eventually shake the world with the breakdown of the Eastern Bloc and the Soviet Union. These developments began with the rise to power of Mikhail Gorbachev in Moscow in 1985, one of whose first decisions was to withdraw Soviet troops from Afghanistan.

This in turn led to the fall of the Afghan communist government and the rise of Islamists in the country. Then in 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, and on Christmas Day 1991, the Soviet Socialist Republic, on which the communists of the old world had built as their aspirations, collapsed. Many of the world's largest communist parties, such as the Italian Communist Party, abandoned their communist ideals altogether and turned to social-democratic politics or even liberalism.

These ideas found support in the Tudeh Party as well. Eskandari died in 1985, and Amir Khosravi and many others left the party, forming a splinter group called the People's Democratic Party of Iran around Mohsen Heydarian. Khavari, however, kept the Tudeh Party in line with traditional Marxism-Leninism. "Even if they break my neck,” the party saying went, “I will not transfer the leadership of the party to the West."

Many other Iranian-origin communist groups issued serious critiques of the Soviet Union and preached new forms of democratic socialism, from Ali Akbar Shalgoni's Rah-e Kargar organization to the old friend of the Tudeh Party, the Fadaiyan-e Khalq. To this day, Khavari's Tudeh Party criticizes all these groups, calling them the "New Left" and maintaining its old position.

According to Khavari, in the aftermath of the Islamic Republic's crackdown on communism, the party's relations with the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc countries were "friendly and warm", especially with Czechoslovakia and East Germany. But "after Gorbachev came to power" and especially in the final years of his rule, these relations came under great strain.

"They tried to influence our party by interfering in its affairs,” Khavari writes, “and determining the leadership of the party. Even when [Boris] Yeltsin was in charge of the Soviet Communist Party in Moscow, they had promised our party's official offices to other people.”

In April 1990, amid the global collapse of communism, Khavari stubbornly convened a Plenum of the party's Central Committee in West Berlin, a city that no longer had a wall. In this meeting, he succeeded in convincing delegates to continue with the old traditions in spite of global changes. The party chose the slogan "Overthrow of the Velayat-e Faqih regime", which is still its slogan today.

A year later, Khavari finally did what the Tudeh Party had avoided for almost half a century: he held the party's third congress. The first and second congresses of the party had been held in Tehran in 1944 and 1948, and now, after all these years, the third event took place abroad in 1991. The fourth to sixth congresses were held in 1997, 2003 and 2012, and the Tudeh Party, now a shadow of its former self, is currently preparing to hold its seventh congress.

Heritage and the Future

Today the Tudeh Party appears to be little more than two postal addresses in Berlin and London, together with the regular issuance of the People's Letter. Tudeh supporters are dispersed across various groups – including the group Rah-e Tudeh, which considers itself a continuation of Kianuri’s party, and the Khavaran Tudeh Party, which in turn criticizes it as "anti-Tudeh".

In his message of condolence, Amouei cited a letter he recently wrote to the Tudeh Party. "I called for efforts to unite the different sections of the Tudeh Party of Iran, which continues to operate under various names," he said. "I hoped and still hope that this organizational fragmentation will give way to unity. With the unfortunate death of Comrade Khavari, the chances of this action being achieved have somewhat diminished, but I hope that those interested in uniting the party will continue to work in this direction."

Khavari's heritage is in fact the preservation of the name and existence of the Tudeh Party, which still commands the recognition of communist parties in India and Greece, which have the support of millions, and even the Communist Party of Vietnam. This preservation, though, has come at the cost of ideological stagnation, a lack of support for the latest developments in the global leftist movement and a lack of widespread activity in the Iranian political and media spheres.

Despite this, many Tudeh Party members believe that when conditions for free political participation arise again in Iran, the Tudeh Party, as it was reborn in in 1979 revolution after a nearly three-decade hiatus, will once again become a party with thousands of members and a serious political force. Only future generations will be able to testify as to whether this hope was founded or not.

Related coverage:

Rafsanjani: The Revolutionary Who Bargained with America and Israel

Communists Tried to Stop the 1953 Coup — But it was “Too little, Too Late”

Neighbors but not Friends: Gilan, Gorbachev, and 8 Other Russian-Iranian Encounters

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments