The death of Iran’s Ebrahim Raisi, president of the Islamic Republic until his helicopter crashed in the mountains of East Azerbaijan on May 19, catapulted Iran into a period of political flux.

Organizing snap elections and identifying Raisi’s successor has become the paramount concern in the Islamic Republic's domestic affaira. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, invoking Article 131 of the Constitution, has meanwhile appointed First Vice President Mohammad Mokhber as the interim head of government.

Khamenei also tasked Mokhber to hold the presidential election within a tight 50-day window – also a constitutional requirement.

The Ministry of Interior, which oversees electoral processes, set June 28 as the voting day for the Islamic Republic’s fourteenth presidential election.

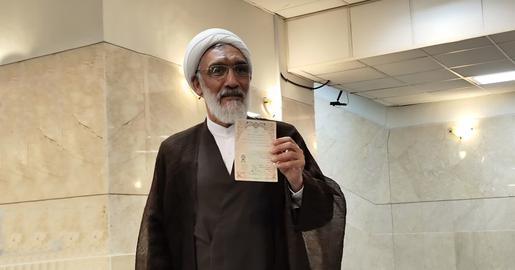

Dozens of hardline and reformist figures have applied to be selected as candidates before registration for the June 28 race closed on Monday. Among the candidates are current and former ministers, parliamentarians, the mayor of Tehran, and four women.

Leading contenders include Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, the hawkish speaker of parliament, and Ali Larijani, a conservative and former parliamentary leader. Saeed Jalili, a former nuclear negotiator, represents the most hardline faction among the registered candidates. And in contrast, Eshaq Jahangiri, who served as first vice-president under President Hassan Rouhani, is the most prominent reformist to stand.

The 80 registered hopefuls now wait for the Guardian Council to vet their candidacy and to determine whether they will be allowed to stand.

One striking entry is that of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Iran's controversial former president, whose ambitions persist despite past political turmoil.

Alongside him are five former vice presidents, most prominently Eshaq Jahangiri, the only former first vice president in the race.

Fifty-three of the candidates are current or former members of parliament. Thirteen have ministerial experience across different presidential administrations. Three serve in the current cabinet: Mehrdad Bazrpash, Mohammad Mehdi Esmaili, and Solat Mortazavi, as well as two current vice presidents, Ghazizadeh Hashemi, vice president and head of the veterans’ institution, and Davood Manzoor vice president and head of Iran’s budgeting and planning organization.

The field also includes four candidates with military backgrounds – some high-ranking soldiers and others with time in the armed forces.

Sixty-six contenders, forming a substantial majority, identify with the Islamic Republic’s fundamentalist camp which advocates for strict adherence to revolutionary ideals and resistance against western influence.

The remaining candidates span other political spectrums, including reformists, moderates, and independents.

But in recent elections, the powerful Guardian Council has systematically barred many reformist candidates from standing; and even though Iran has regular presidential and parliamentary elections, the country's political system gives Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei ultimate authority.

Khamenei was selected as Supreme Leader in June 1989 – a position granted for life. He is the country’s highest-ranking political and religious figure and his decisions supersede those of elected officials.

Many analysts argue that this structure limits the impact of the voting process. Key policies and candidate selections are influenced by the clerical leadership, leading some experts to view the elections as largely ceremonial exercises, offering only a veneer of democratic choice.

Declines in voter turnout in Iran’s most recent parliamentary and presidential elections seem to confirm this analysis.

A Snap Election

The Islamic Republic had already seen three early presidential elections before Ebrahim Raisi’s sudden death.

Two presidents, Abolhassan Bani Sadr and Mohammad Ali Rajaei, both of whom served in the early years of the Islamic Republic, were unable to complete their four-year terms. One was removed from office and the other was assassinated. Ali Khameini was himself president, meanwhile, when the Islamic Republic’s first supreme leader, Ruhollah Khomeini, passed away in 1989, leading to his appointment to Iran’s highest office.

The subsequent presidential election was held on July 28, 1989, resulting in Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani becoming president on August 3.

Presidential terms in Iran last for a fixed four years – with presidents eligible to serve only two consecutive terms. (Ahmadinejad served two terms, from 2005 to 2013, but Iran’s constitution does not bar former presidents from serving a third term as long as it is not consecutive to the second.) Article 131 of Iran's Constitution allows two months for authorities to hold early elections. Given the possibility of a runoff, between leading candidates, this timeframe is typically factored into the election schedule.

The upcoming election process began with candidate registration from May 30 to June 3.

From June 4 to June 11, the Guardian Council will vet candidates, with the approved list to be announced on June 11.

Campaigning runs from June 12 to June 27, followed by a one-day campaigning blackout. Voting is scheduled for June 28.

This compressed 30-day schedule covers the entire process from registration to voting day. No specific timeline is set for vote counting and the announcement of the result.

If no candidate secures a majority – 50 per cent plus one vote – a runoff between the top two candidates will be held a week later, tentatively on July 5, to determine Iran's ninth president.

Comparing this timeline to standard election procedures reveals the tighter schedule on this occasion. The 2021 presidential election, for instance, spanned about 110 days from announcement to result. Campaigns lasted about 20 days in that election and the Guardian Council had 5-10 days to vet candidates.

But other details, such as the period during which registrations were open, the campaigning blackout period, and runoff timing, are similar in both scenarios.

Who Can Run?

Article 35 of Iran's Presidential Election Law stipulates that candidates must be religiously devout, political figures, of Iranian origin, and citizens of the Islamic Republic.

The candidates must also demonstrate competence, resourcefulness, a commendable record, trustworthiness, piety, and belief in the Islamic Republic's foundations and Iran's official religion of Shia Islam.

The law further specifies that heads of the three branches of government, the first vice president, deputy parliament speaker, Guardian Council members, ministers, parliamentarians, vice presidents, and mayors of cities with over two million population are eligible to run.

Presidential candidates must also be between 40 and 75 years old at the time of their registration.

Questions have arisen regarding the eligibility of Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, the speaker of parliament, who after Raisi’s death was appointed to a three-member council entrusted with conducting the election. His dual role has sparked concerns about potential conflicts of interest.

But on May 25, the deputy official of the Guardian Council's Research Institute clarified: "Legal analysis shows that members of the three-member council overseeing the presidential elections are not barred from candidacy ... Only election executive officers are prohibited from running."

What is a ‘Man'?

A long-standing ambiguity persists in interpreting the term "man" (in Arabic, "رجل") from Article 35 the election law.

The term, often translated as "statesman" or "political figure," has never been definitively clarified by the Guardian Council regarding whether it exclusively refers to males or could include women.

By law, women are allowed to stand for president; in reality, their possible candidacy hangs on this interpretation.

Azam Taleghani, a veteran reformist politician and journalist, and a woman, registered to run in every presidential election from 1997 until she died in 2019. She was rejected each time by the Guardian Council.

On May 29, a day before registration began, the Guardian Council's spokesman released their 2021 resolution detailing the definition, criteria, and conditions for recognizing a candidate's political, religious, managerial, and resourcefulness qualities.

While the resolution elaborates on who qualifies as a "statesman," it maintains a conspicuous silence on whether women can be candidates, a question that has remained unanswered for over four decades.

On the same day, Iran's Interior Minister gave a vague response to a question about women's registration: "We will register anyone who comes and wants to register according to the legal conditions."

What is the Guardian Council?

Iranian candidates running for any election must be vetted and approved by the 12-member Guardian Council.

Six members of the council are directly appointed by the Supreme Leader. The remaining six are nominated by the head of the judiciary and approved by parliament. The head of the judiciary is directly appointed by Ali Khamenei.

Iran's parliament, meanwhile, despite its constitutional mandate, is a largely constrained and ineffective institution. Its impotence stems from the existence of powerful, overreaching entities that undermine its authority, from the election of representatives through the drafting of laws, even after parliament's formal establishment in each electoral cycle.

Chief among the institutions that overshadow the elected parliament is the unelected Guardian Council, which has, in the decades following Iran's 1979 revolution, gradually exerted complete control over parliament and assumed a substantial role in restraining its members.

The Islamic Republic's original constitution assigned the Council three duties: ensuring legislation adhere to Islamic Sharia law, interpreting the constitution, and overseeing elections and referendums. But the Council has wielded these powers in ways that have neutered parliament.

Recurring disputes between the two bodies over approved laws, for instance, led to the creation of a new arbitrating entity; the Expediency Discernment Council. The Guardian Council, initially designed to resolve deadlocks, transcended that role and became a supra-parliamentary institution that, in practice, even legislates of its own accord. And the authority to "interpret the constitution" has enabled the Guardian Council to interpret and exercise its powers in an expansive and dominating fashion.

Such a broad interpretation has stripped parliament and even the executive of any capacity to establish alternative legal understandings that might reflect the people's will.

And over the years, the Council's election oversight has morphed from an observational role to a discretionary one, allowing it to control the composition of representatives during elections before each parliamentary session and new presidential administration. The Council’s role has even continued after elections; in one instance, a parliamentarian from Isfahan was disqualified post-election.

But the constitution's drafters seem to have envisioned a different scope for the Guardian Council's supervisory duty. Article 99, ratified in 1980, said only: "The Guardian Council is responsible for supervising the election of the President, the election of the Parliament and referendums."

A decade later, during constitutional revisions, oversight of the Assembly of Experts elections was added. The Assembly of Experts is a popularly-elected 88-member deliberative body of Islamic scholars who, in theory, oversee the Supreme Leader.

The Guardian Council's current practices are, at any rate, in stark contrast with its original and more limited mandate. The expansive interpretation and application of powers has transformed it from a constitutional guardian into a gatekeeper – key to deciding who can participate in Iran's political process.

(Some of) The Contenders

Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, 62

Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf is a hardline conservative in Iran's parliament and a vocal proponent of rapid modernization.

His political career spans decades, reflecting his rise through Iran's military and civil institutions. During the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, he served as a commander in the elite Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. His career as a Revolutionary Guard general left a legacy of controversy: in 1999 he supported a violent crackdown on protesting university students.

After the war, Ghalibaf transitioned to law enforcement, becoming Iran's chief of police. In this role, he was known for his tough stance on dissent and his efforts to modernize the force. In 2003 he also ordered live fire to be used against protesting students.

Ali Larijani, 67

A prominent politician who has shifted from a hardline to a more moderate stance.

Larijani served as culture minister and then parliamentary speaker, until 2020, and played a role in securing the 2015 nuclear deal with world powers, which has made him a target for hardliners.

Larijani's potential presidency raises questions about his alignment with Ali Khamenei's vision. If Larijani becomes president, because he is on a softer end of the conservative spectrum, he risks facing a fate similar to that of Hassan Rouhani, who was eventually sidelined because of the Supreme Leader’s disapproval.

But Larijani is known for being less forthright than Rouhani and may avoid openly criticizing the leadership to maintain his position.

Where Larijani might fight a base of supporters, however, remains unclear. The reformists have said they will back a dedicated candidate – indicating that Larijani is unlikely to receive the same level of support from reformists that Hassan Rouhani did in 2013.

Saeed Jalili, 58

A hardline politician representing radical factions, Jalili was Iran's top security official and chief nuclear negotiator from 2007 to 2013.

A veteran of the 1980s Iran-Iraq war, he opposes rapprochement with the United States and insists that Iran can thrive without a new nuclear agreement or sanctions relief.

Jalili withdrew from Iran’s 2021 presidential election and then became a key player behind the scenes for Ebrahim Raisi’s government. Many of his associates then spread through different parts of the Raisi administration. Iran’s domestic media refers to these associates as “Jalilion” – confirming a sense of his ongoing importance.

His role in Raisi’s government became so pronounced, at one point, that the newspaper Etemad published an article titled "Saeed Jalili's Empire in the President's Government."

Eshaq Jahanigiri, 66

A reformist who served in the 2013-2021 centrist government of Hassan Rouhani and the 1997-2005 reformist administration of Mohammad Khatami.

Jahangiri withdrew his presidential bid in 2017 – in favor of Rouhani, as the then-president campaigned for his second term – and later was thwarted by hardliners ahead of the 2021 election. He wants to revive the nuclear deal and ease domestic repression.

All of the Contenders

- Independent - Mohammadreza Sabaghian

- Conservative - Abbas Moqtadaei

- Reformist - Ghodrat Ali Heshmatian

- Conservative - Saeed Jalili

- Conservative - Ali Larijani

- Conservative - Mahmoud Ahmadi

- Conservative - Mohammad Khoshchehreh

- Reformist - Abdul Naser Hemmati

- Conservative - Seyyed Ahmad Rasoulinejad

- Independent - Vahid Haqqanian

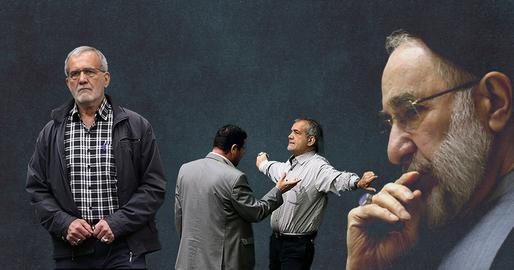

- Reformist - Massoud Bezeshkian

- Conservative - Habibullah Dehmordeh

- Conservative - Alireza Zakani

- Conservative - Mohammadreza Mirtajuddini

- Conservative - Zohreh Elahian

- Conservative - Fadahosein Maleki

- Conservative - Mohammad Mehdi Esmaili

- Conservative - Masoud Zaribafan

- ---- - Hossein Afsharzadeh

- Conservative - Mahmoud Ahmadinejad

- Conservative - Hossein Ali Ghasemzadeh

- Reformist - Mahmoud Sadeghi

- Conservative - Sadegh Khalilian

- Conservative - Seyyed Mohammad Moghimi

- ----- - Iraj Shahverdi

- Conservative - Mohammad Hassan Qadiri Abyaneh

- Conservative - Hassan Mohammadyari

- Conservative - Mjtaba Mahfozi

- Reformist - Shahriar Heydari

- Reformist - Ali Sovfi

- Conservative - Mohammad Ebrahimi

- Conservative - Hossein Mirzaei

- Conservative - Gholamhossein Rezvani

- Reformist - Mohammad Shariatmadari

- Conservative - Jalil Jafari

- Conservative - Ghani Nazari

- Conservative - Elias Naderan

- Reformist - Hassan Sobhani

- Conservative - Hassan Kamran

- Conservative - Ahmad Akbari

- Reformist - Hamideh Zarabadi

- Conservative - Mohammad Nazimi Ardakani

- Conservative - Seyyed Ghasem Jasmi

- Conservative - Alireza Varnaseri

- Independent - Hamid Karimi

- Independent - Ali Azari

- Conservative - Mohammad Reza Eskandari

- Conservative - Vahid Jalalzadeh

- Conservative - Ardeshir Motahari

- Reformist - Eshaq Jahangiri

- Independent - Mohammad Vahdati

- Conservative - Hassan Nowrozi

- Conservative - Mohammad Rouyanian

- Conservative - Hossein Garoosi

- Reformist - Mahdi Sheikh

- Reformist - Mohammad Ali Vakili

- Conservative - Mohsen Kohkan

- Conservative - Mohammad Mehdi Zahedi

- Reformist - Mustafa Kavakebian

- Conservative - Mohammad Hasan Nami

- Conservative - Mostafa Pourmohammadi

- Reformist - Asghar Salimi

- Conservative - Shamsuddin Hosseini

- Conservative - Alireza Afshar

- Conservative - Zargham Sadeghi

- Conservative - Hajar Chenarani

- Conservative - Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf

- Independent - Abdul Rahim Baharvand

- Conservative - Akbar Nikzad

- Conservative - Seyyed Ahmad Mousavi

- Conservative - Ebrahim Azizi

- Reformist - Abbas Akhundi

- Conservative - Davood Manzoor

- Conservative - Seyed Ali Nishabori

- Conservative - Mehrdad Bazrpash

- Independent - Ali Vafghchi

- Conservative - Amirhossein Ghazizadeh Hashemi

- Conservative - Seyed Solat Mortazavi

- Conservative - Ali Nikzad

- Conservative - Rafat Bayat

comments