Last month I attended a webinar organized by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) and IranWire. Dr Edna Friedberg, a historian at the museum, spoke of the project known as the Final Solution in Nazi Germany.

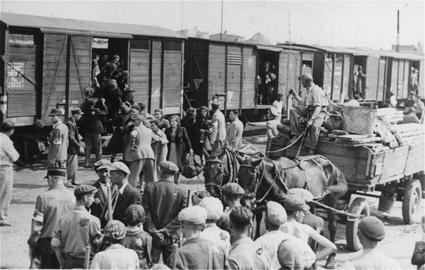

The "Final Solution to the Jewish Question” was another name for the deliberate, systematic and pre-planned mass murder of European Jews conducted by Nazi Germany, led by Adolf Hitler with the help of collaborators in various European countries during the Second World War, from 1941 to 1945. It was during these years that the Nazis and their collaborators dedicated massive resources, in a targeted and systematic way, to the machinery of killing.

What caught my attention in the webinar was the degree of order and intention in the gradual organizing of this lethal architecture, and the depth of the systematic cruelty and thirst for blood. What came out of the webinar was, for me, a ‘Danger’ alert: an ideological and tyrannical regime that has always been centered around violence has, certainly, the potential to carry out genocide. In other words, as the webinar went on, I kept thinking: In a country like Iran in the grip of the Islamic Republic, we sometimes believe we can’t see any worse. We think we’ve seen it all: policies so violent we can’t imagine going beyond them. But we must always remember that such a government can – and is actively trying to – work with its guaranteed supporters to make its acts of violence bigger and more complex.

Dr Friedberg explained to us, in details that were often hard to hear, the process that the so-called Final Solution followed, as well as the decision-making and methods adopted to make this mass execution so orderly and systematic. I will present just a few short examples here.

Did Nazi Germany intend to conduct mass murder of European Jews and other vulnerable and minority groups from the very outset? Today, this is a topic of debate amongst historians and other experts. But, Dr Friedberg said, “What is known without question is that the decision to commit genocide, after which there was no turning back, was made sometime in 1941.”

In response to a question about early Nazi efforts to push Jews out of Germany before the killings began, she said: “Even the policy of forced or pressured immigration always had inconsistencies… On the one hand, life in Germany was made impossible, uncomfortable, difficult [for Jews]. I think of it a slow strangulation of German Jews through economic measures and restrictions on society. But on the other hand, it was also made almost impossible to leave [due to the financial cost].”

In another part of the webinar, Dr Friedberg explained the evolution of the Nazi killing centers: “We know that – and again, there was not one document, but – Nazi Germany was experimenting with methods of mass killing that predated the mass killing of Jews… kind of tryouts of techniques. It started with the systematic murder of people with mental and physical disabilities. That’s where some of the techniques [were developed], including some of the first gassing, and the use of crematoria to burn the bodies of people who were living in what we would today call a psychiatric hospital. They were killed sometimes by forced starvation, sometimes by lethal injection. There is a direct line between this so-called ‘euthanasia program’ and the mass killing of Jews later.”

There is much one could say about the death camps, the mass shootings of Jews around Europe, how Jews were forced to watch the killing of their loved ones before digging mass graves for themselves and being shot into them, the mobile death machines in which Jews were gassed, ultimately the killing centers, and all the other parts of this terrifying, orderly and intricate process. Here I’ll limit myself to the summary points mentioned above.

As I wrote earlier, the painful details of the Final Solution were, for me, akin to a warning, and a reminder that one thing is always shared between authoritarian, ideological and discriminatory governments, despite their obvious historical and political differences. There is always a way to make it worse; conditions can always become graver, more violent and bloodier.

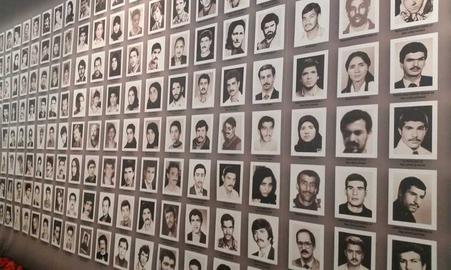

I think of today’s Iran. Of the people of my generation who have lived for a long time with daily news of killings, executions, imprisonments and torture. In the UN’s most recent annual report about the situation of human rights in Iran, which has been approved by the UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, concern is raised about the rate of executions in Iran: at least 105 people were executed in the first three months of 2022 alone.

During the webinar, I spoke of the Baha’is of Iran. They have kept to their pacifism and moderation despite all the hardships, and even after they have been forced to live in a prison built for them by the Islamic Republic as an unrecognized religious minority. After the worst years of systemic discrimination, arbitrary detention, murder and forced disappearances, they still don't even have the right to enroll in a university. Their shops are forcibly closed.

I thought of Kurdish friends who, in my long years of human rights activism, have shared with me stories of their near-impossible political and economic status in Iran due to the state’s oppressive, discriminatory policies. I thought of their memories of seeing local shootings as children; of how sad their lives were, whether in Iran or Iraq, while the Iran-Iraq War was raging; of how their fates had been sealed in 1979, even if they were only children back then, when Khomeini issued the fatwa for ‘struggle against the Kurds’.

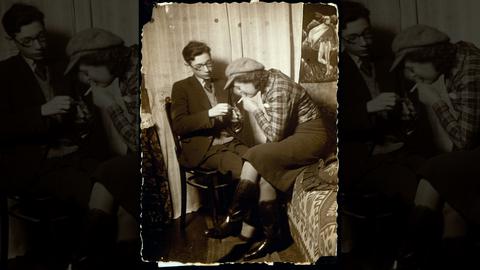

As I listened to the words of the museum’s historian, I thought of my own childhood and the mass murder of intellectuals, the so-called chain murders, of the 1990s in Iran. It felt then as if stories of nightly disappearances, or killings, of our family friends, through the cut and thrust of a knife or other means, were just part of the fabric of our daily lives, and our nightly terrors.

I remember when I was arrested at the age of just six, along with my parents and my sister, because I had attended a ‘mixed party’ in which women had been present, without their hijabs, next to men. I was in prison for a few hours. And at every other party throughout my childhood, I heard about people’s friends and loved ones who had been tortured or executed in prisons.

I’d shout about the big prison we were all living in. I’d tell other kids that they were killing people in the prisons, and that I wanted to die. Why should a six-year-old have to hold the knowledge that her government is killing her people? I thought of my generation, born amid the carnage of the 1980s, without even knowing the full extent of the violence perpetrated by our government in our own homeland. Today we inherit a country full pain. I thought of those killed during the Green Movement, November 2019, and dozens of other protests; of courageous, justice-seeking bereaved mothers who have now become a voice for the voiceless.

The webinar has reawakened in me a perpetual fear: that a government like the Islamic republic can be always more violent, more murderous. As Dr Friedberg shared her knowledge with us, I thought that maybe we could learn from the horrific experience of the Final Solution and the Holocaust, and consistently work to reveal the details and mechanisms of discrimination, torture and killings in the Islamic Republic, through persistence and attention to detail. By doing this, we might cut the government short in its recurrent, expansive bouts of violence.

Sometimes, one feels clueless: Why don’t we see improvements to the situation in Iran despite years, generations, of human rights activism? The truth is that there is no other way than this: documenting, and tirelessly revealing, the violence the government prefers to conduct in the dark. This is how we reduce its power.

In the hope that one day, we’ll be able to live without fear and oppression, in calm and peaceful coexistence, not only having to defend our own rights but also learning about the rights of others so our historical and cultural prejudices do not become ground for the growth of discrimination, which can turn lethal. Ultimately, each of us has a duty not only to seek justice for the crimes of the past, but to work to prevent the spread of new violence.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments