“I am a protester! […] I am a victim of [your injustice]...Who are you [to act] like ghosts behind curtains and issue orders [arbitrarily]?...Mr Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance! I can’t take this [injustice] anymore! I declare war against you and your organisation! Look! Here is my chest – Come and kill me! Destroy me! Do what you want to me! But know that I will seek my rights with my life!’

In an emotional and eerily prescient video message, some 18 months before he and his wife, Vahideh Mohammadi, were savagely stabbed to death on Sunday, October 15th, 2023, in their home in a Tehran suburb, Dariush Mehrjui, pulled at his chest and railed against the Islamic Republic and its stifling culture policies. Dariush Mehrjui, a scholar of cinema studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, in the 1950s and 60s, became known as a founding member and doyen of the New Iranian Cinema movement. With his 1969 film The Cow (Gaav), winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1971, he put Iran as a “film-nation” on the map. According to Dariush Mehrjui himself, his film The Cow in a way single-handedly saved Iranian cinema from completely disappearing under the Islamists who took over Iran after the 1979 revolution toppled the Shah. In an interview with me (S. Rahbaran, Iranian Cinema Uncensored 2016, pp.79-101), he pointed out that the burning down of Cinema Rex, which killed over 600 viewers in the city of Abadan, was a life-threatening sign for cinema: “At the beginning of the revolution, Iranian cinema was nothing! All the studios, film institutes and film theatres were dead…Remember that one of the first revolutionary acts that people committed was to burn down a cinema. Why? Because they thought that cinemas were centres of immorality; the core of vulgarity, corruption and Western decadence. So, we entered a complicated stage: fanatics burning down cinemas and intellectual filmmakers saying that they wanted to make films! It was a most precarious situation. We were on a knife’s edge.”

Were it not for Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini watching The Cow by chance on TV, Mehrjui believed, cinema might have died in Iran - just as it did in Saudi Arabia, where theatre movies were closed from the early 1980s onwards before being reopened in 2018 (S. Nordwall, VOA, 04.04.2018): “No one knew what to do until, by chance, Ayatollah Khomeini, the leader of the 1979 revolution, watched my film Gaav on television. The next day he made a speech and said, ‘We are not against the art of cinema at all. We are in favour of educational and cultural films such as this film, The Cow.’” Mehrjui’s role in the resurrection of the New Iranian Cinema in the Islamic Republic has always been a point of contention, especially amongst certain Iranians in the Diaspora. This has become particularly clear from the varied reactions to his savage assassination, with some going as far as saying that it “served him right.” According to these people, Mehrjui was not only believed to be an “appeaser” of the regime but also an active part of the anti-imperialist Marxist ideology that found its ally in the anti-Western Islamist school of thought, which directly contributed to the onset of the brutal and backward theocratic system of government in Iran.

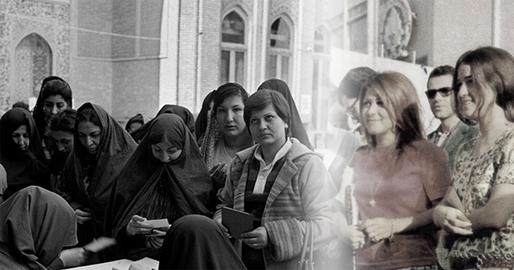

The fact is that the founders of the New Iranian Cinema in the 50s and 60s had left-leaning (sometimes downright leftist) inclinations. These inclinations were very typical in the global flora and fauna of the “art world” in those days. Iran, being very much in the midst of that world - not least because of the Pahlavis’ enthusiasm and subsidies for culture - was no exception. Despite all this, Mehrjuii always saw himself and his art as a part of Iran, its people and its culture. Iran was where he got sustenance from. And like many of his colleagues in Iran who continued to stay, for fear of losing that creative connection between their country and their art, he too was forced to accept the same role that most artists in totalitarian regimes have to play; namely, that of the engagé intellectual, while simultaneously working under an oppressive system of government that restricted artistic and intellectual activity. Mehrjui told me that he saw it as his artistic mission to show the injustices in such a society: “I am always pulled towards those who don’t accept oppression and extortion. For instance, before the revolution I concentrated on the oppressed and disgruntled working class, and my ideology and philosophy were based on Marxism and the socialist ideologies of the time…After the revolution the class I fought for became dominant, so addressing that group was ridiculous. Now I concentrate on the middle class, the bourgeois – especially the bourgeois women. I mean, universally, women do not have the same rights as men, but in the post-revolutionary Iranian society and under the pressure of religious fanaticism, Iranian women face worse deprivations than women elsewhere. Especially the compulsory hijab in Iran has become a symbol of oppression and deprivation globally.”

Through his artistic medium, Mehrjui wasn’t only interested in showing the injustice of compulsory hijab that women in Iran had to endure, but also wanted to observe what a woman can do in such a situation; what means of manoeuvring she has. He has made many films that address women’s issues in Iran, such as Sarah (1993), Pari (1995), Leyla (1996), Banoo (1998) and so on. In these films he shows that he was in fact a pioneer of women’s rights in the Islamised Iranian society long before the Woman, Life, Freedom Uprising.

The conundrum that Mehrjui and his comrades-in-arms faced since the founding of the Islamic Republic was how to carve out intellectual and artistic spaces within the censorship restrictions put in place by the Islamic Republic and at the same time guard their artistic and intellectual honesty. This was and continues to be extremely difficult in a system that not only restricts art, but also uses it as a means of propaganda. That made artists such as Mehrjui a target for both the proponents of the Islamic Republic and its adversaries. Both of these groups criticised him and his colleagues for continuing to stay and work in Iran. He was attacked for being both a non-conformist and an appeasement artist. Mehrjui told me that this was one of the tactics of Iran's rulers, leveraging both of these sentiments to create a large “double” divide in a sense – between artists and their works on the one hand and the audience on the other. This divide is the biggest tragedy affecting the film industry in Iran after the Islamic revolution. In the context of the Woman, Life, Freedom Uprising, this tragic divide is not only damaging the film industry but also the unity of the opposition against the Islamic Republic.

After his and his wife’s dead bodies were found by their daughter, the police immediately released a statement saying that the crime had been committed by an unknown person or persons, and for unknown reasons. However, judging by the storm of anger and resentment, it is clear that nobody in Iran believes this statement. Faced with the greatest wave of protests since 2009, the Islamic Republic has resorted to increasingly brutal methods of oppression in an effort to stem the Woman, Life, Freedom Uprising. Being blinded, jailed, tortured, poisoned and killed is what protestors risk every time they openly raise their voices against the Islamic Republic. Assassinations are on the everyday agenda. Most Iranians view this “mysterious murder” in the same light as the assassinations of public intellectuals in the 1990s - infamously known as the “Chain-murders.” The death of Mehrjui and Vahideh Mohammadi serve as a particularly gruesome reminder of the double murder of Dairush Forouhar and his wife Parvaneh - another intellectual couple that was killed in an eerily similar way 25 years ago. Dariush Forouhar - Mehrjui’s namesake - the leader of the Iran National Party at the time, and his wife Parvaneh were butchered by savage stabbings in their home, too. The “mysterious assailants” were never found and tried. Now as then, it is widely believed in Iran that the Islamic Republic aims at scaring public intellectuals: “No one is safe; you won’t be spared; even the great Master Dariush Mehrjui wasn’t!” – that is the message.

In the last days of his life, Mehrjui was collaborating with Hassan Solhjou, a filmmaker and a senior producer of BBC World Service, on a (unfinished) documentary in which he passionately expressed his opposition to the Islamic Republic and compulsory hijab by beseeching his wife to remove her head covering. After some deliberation she does and they both laughingly hang the pink scarf from a tree. Sadly, it took his and his wife’s bloodied corpses to show that Mehrjui stood on the right side of history.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments