Berlin is a city of memorials. But this has not always been the case. The post-war years were characterized by heated national debates about how Germany should remember the horror of its past. And these debates continue to this day.

Successive German governments have been either reluctant to create memorials or uncertain about how best to do so - but individuals have led the way. Dr Klaus Mueller, the Representative for Europe at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) is keen to emphasise that most memorials have come about as the result of the efforts of a small number of people, who determinedly made the case for its need.

In Germany, the creation of a new memorial has the power to spark a nationwide discussion. These are personal and political questions.

How has the country dealt with its responsibility for the murder of European Jews? Has it reckoned with the Nazis’ persecution of suppressed minority groups such as Roma and Sinti, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses or people with mental and physical disabilities? Post-reunification, what message did the German government want to send to the world about its attitude towards the country’s past? What do memorials mean for victims?

IranWire’s Maziar Bahari visited Berlin to meet with Mueller to make a series of short films as part of the Sardari Project. These films are published on IranWire and associated social media sites in English and Persian. Dr Mueller works as an international consultant for cultural institutions, advising museums, foundations and NGOs, and his research focuses on Holocaust documentation and education, antisemitism, and genocide prevention.

Bahari and Mueller spent several days visiting six different sites of memorial across Berlin to discuss how these memorials came into being and the significance they hold today and potentially for the future.

Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp Memorial and Documentation Center

Situated just 35 kilometers north of Berlin, Sachsenhausen’s proximity to the capital of Germany gave it a special position within the network of concentration camps that developed quickly after the Nazis’ rise to power in 1933.

Mueller notes that arriving at the camp in 2023, “What you first see is greenery, flowers and trees. It's very quiet. But this is the same place where tens of thousands of people were imprisoned, experiencing a horror that goes beyond our imagination.”

Today very little is left of what once stood here. This is in part due to the Nazis destroying evidence at the end of the war - but it is also due to the way governments in East and West Germany turned former concentration camps into memorials, sometimes removing barracks and other defining features.

The aim of preserving Sachsenhausen is to localize the unprecedented violence and murder that happened there. According to Mueller, the memorial, which opened in 1961, tells “individual stories, so we understand these were not just victim groups, they were individual people”. And, even when little physical evidence remains, preserving a physical place gives visitors a space to think about what happened.

Of the estimated 44,000 camps across Europe, only 6,000 have been preserved. Mueller argues that by documenting and exhibiting what happened at camps like Sachsenhausen, “we can start to grasp that universe, which is so far removed from us in one way, and on the other hand, is just two generations away.”

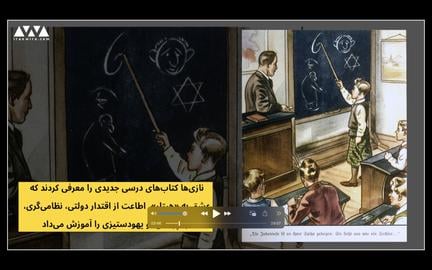

One reason this matters is that “this was not just the result of a small Nazi elite, and many ordinary people in one way or another supported it, joined it or looked the other way, completely indifferent to the suffering all around them.”

The question, as Mueller sees it, is what can Germany and the rest of the world learn from what happened? “By understanding these mechanisms, by understanding the structures that enable and facilitate mass murder, we hopefully can create mechanisms to prevent them in the future.”

Remembrance of the Nazi past remains vitally important today.

According to Mueller, “there is a growing interest within the younger generation to make sense of what happened and they need to find their own ways of doing so. Memorials help them to do that.”

“Unfortunately, if we look at Europe in 2023, we see that antisemitism has not left Europe. Scapegoating minorities has not left Europe. Fascism has not left Europe.”

“So looking back is not just a philosophical question, it's a dire political need. What if we fall back into the dark period out of which we came?”

Neue Wache

Neue Wache, meaning the “New Guard”, is a neo-Classical building in Berlin’s center, first built at the beginning of the 19th century as the guardhouse for the royal palace across the street.

It has since served many different functions – first as a memorial for those soldiers killed in the Napoleonic Wars and later for those German soldiers who had fallen in World War One. During the era of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), the memorial was dedicated to “victims of fascism and militarism”. In 1969, an unknown soldier of the Second World War and an unknown concentration camp prisoner were buried at the site. Following Germany's reunification, it became a national memorial for the “victims of war and tyranny” and it has remained in this latest iteration since 1993.

Mueller sees this “very generic form of remembrance” as emblematic of “the kind of remembrance Germany had in the early 1990s”, where very different groups - including victims and perpetrators, victims of the Holocaust and German soldiers - were remembered together.

He is clear on the limitations of this approach. “It's not possible to commemorate perpetrators and victims in one place together. It’s not only insufficient, it's totally wrong. It doesn't make any sense.”

According to him, it “blocks a form of dignified memory, but also simply the historical truth.”

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe

After almost twenty years of public discussion, the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe was finally inaugurated in 2005.

Although discussion about creating a memorial for the Jewish victims of the Holocaust first started in the late 1980s, it took almost ten years for the German parliament to agree to the idea, and many more before the memorial was finished.

According to Mueller, there was “always a dissatisfaction with how the country dealt with its barbaric history”. He said, “especially in the post-war years, the German population developed the idea that this was all done by a few Nazi leaders, who were evil seducers of the innocent German people.” This narrative “nurtured the desire not to remember, not to look back.”

In the late-eighties, a small group formed and made the argument that Germany needed a central memorial to honor the six million Jews who were killed by the Nazi regime.

This eventually opened a public discussion. Some argued against giving it such prominence in the capital. But the main question was about how the newly reunified Germany would behave. “Would it feel responsible and take on the responsibility for Holocaust remembrance in Germany and really make it a cornerstone of its policies, of its thinking, of its ethical orientation?”

All of this took place in the context of the reunification of East and West Germany, particularly with the capital returning to Berlin, which had been the capital of the Third Reich and the center for the planning of the “Final Solution”.

According to Mueller, this raised the question of how Germany moves forward “if we don't give the past a more prominent and more visible space.” Both inside and outside Germany, the process of reunification was followed with concern: what would it mean for Europe? What would the country focus on?

Mueller considers this memorial a form of response to these questions and a “very clear gesture” that Germany’s past would “orientate its future government policies”.

Once the German government had agreed, two competitions followed to decide what it would look like. The memorial, which came as a result, is remarkable and a completely new form of monument. “There's no entrance. There's no exit. There is no name. It doesn’t say this is a memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe. There's nothing that points to the perpetrators.”

“So it's a monument that invites its visitors to think for themselves,” Muller said. “That is also the criticism, of course, that it is not didactic. It doesn't give you the answer. What it basically says is: this is your question.”

Mueller points out that the memorial is made of concrete blocks. “If you don't have public discussions, public remembrances and continuous engagement by civil society, this will eventually just be a bunch of stones.”

Memorial to the German Sinti and Roma Victims of National Socialism

The memorial to Roma and Sinti victims of National Socialism both offers a space for visitors to go and think, as well as the chance for people to educate themselves about this part of Germany’s history. This ethnic minority is made up of distinct groups called “tribes” or “nations”. The Sinti generally predominated in Germany and western Europe. The Roma predominated in Austria and eastern and southern Europe.

The Romani people were among the groups that the Nazi regime and its partner regimes singled out for persecution and murder before and during World War Two. The exact number of Romani people that the Nazi regime and their allies murdered is unknown. It is estimated that at least 250,000 European Roma were killed during World War Two. But the number may be as high as 500,000.

Situated close to the German parliament, it consists of a small pond with a triangular stone at the center where a fresh flower is placed each day. Around the edge of the water is the poem “Auschwitz” by Italian Roma Santino Spinello in English, German and Romani: "Sunken in face / extinguished eyes / cold lips / silence / a torn heart / without breath / without words / no tears”.

The memorial also consists of a glass wall, offering a chronology of what happened to Roma and Sinti victims of the Nazis, a story which is sometimes excluded from public discussions. Mueller said “It's important that when you visit this memorial you not only remember, but you also learn something.”

This memorial is distinct because it has only one point of entry and exit, which, according to Mueller, ‘“creates a sense of being in a place, a quiet place, a place where you can feel. It is also about respect.”

Plans for building the memorial started in the 1990s. Due to construction problems and limited funding, it took a long time and was finally inaugurated in 2012.

Mueller describes the opening as a moment of “relief and pride” for the Roma and Sinti community who were finally receiving recognition. “It reminds you, in the end, we are not talking about groups. We are talking about individuals, their families, their lives.”

With memorials like this in the center of Berlin, people may be passing by and come across them by accident. To Mueller, this is an important aspect of what a memorial is trying to do. The Nazis committed their crimes in broad daylight before people’s eyes, and memorials should reflect this fact. “Remembrance happens in the midst of society where you live, it's not somewhere you go.”

Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted Under Nazism

This monument, opened in 2008, is unusual in that it has a double mandate. The first and most important aim was to remember and honor the gay victims of National Socialism. But the German parliament also believed that, because of its history, Germany has a special responsibility to actively oppose abuses targeting LGBT people across the world in the present day.

As a gay man growing up in West Germany, Mueller didn’t learn about the Nazis’ persecution of gay people until he started studying in his twenties. This would later become the focus of his work.

Germany’s understanding and acknowledgement of this topic has changed greatly over the course of Mueller’s career. In the post-war decades, historians and memorials ignored the Nazi persecution of LGBT people as it was not regarded as a Nazi injustice. Paragraph 175, a German statute that criminalized sexual relations between men, remained in force in its Nazi version in West Germany until 1969, with about 100,000 men investigated and half of them convicted, including gay survivors who were sentenced as ‘repeat offenders’.

Researchers finally began to document the treatment of gay people under the Nazis for the first time in the 1980s and 90s. The monument was a key moment for the German government in publicly acknowledging this history.

Mueller is clear that while there has been a huge shift, the German government did not recognize what happened to gay men, who were imprisoned and incarcerated in camps during the Nazi period, while they were still alive. This means the vast majority of gay survivors were never acknowledged as victims in their lifetimes.

As with the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, this memorial was designed as the result of a competition. The winning entry became a memorial that projects a film inside. Looking through a small window reveals a short clip in a loop showing two men kissing.

This video led to an engaged and heated discussion - particularly from the lesbian community, who said the memorial excluded them from the narrative. As the memorial’s double mandate also concerned the validation of equal rights for LGBT people today, the inclusion of lesbian women in its visual language found broad agreement and was implemented in the next video produced for the memorial. Now the video changes every few years to show a different short film.

The monument has been vandalised numerous times since its inauguration.

T4 Memorial for the Victims of the Nazi “Euthanasia” Programme

People with mental and physical disabilities were a further group who at first received little recognition for the persecution they suffered under the Nazis. This is why it is so important that the T4 memorial is not only a place to remember the victims of the Nazi “euthanasia” programme; it is also a source of information and education.

The monument to the 250,000 to 300,000 disabled patients who were victims of the Nazi ‘’euthanasia” program stands at Tiergartenstrasse 4 (T4), the street address where the program’s main office once stood.

The memorial gives information about what happened and how, and tells individual stories of victims who were taken from their care facilities, and underwent forced sterilizations or were murdered by physicians and nursing staff of T4 killing centers and “euthanasia” sites in Germany and in German-annexed territories. The exhibition is written in language that is accessible for people with a range of reading abilities.

Mueller points out that this victim group - while for the most part were German Christians - did not fit into the Nazi ideology of racial hygiene. When someone was living in an institution and unable to work, they were seen as worthless by the Nazi regime and were killed.

The T4 memorial was created after a small group of people made the case that mentally and physically disabled victims needed to have an adequate memorial - as seen for others.

The group came together, conceived an idea, and the German parliament accepted it. In 2014, the memorial was inaugurated in front of the Berlin Philharmonic in the same place where officials planned and organised the T4 Aktion, which involved the systematic killing of people with disabilities by the Nazis.

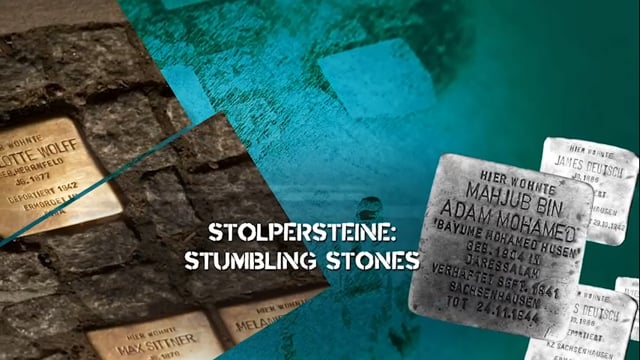

Stumbling stones (Stolpersteine)

The Stumbling Stone initiative was started by German artist Gunter Demnig in 1993, but it has since taken on a life of its own. There are now approximately 100,000 stumbling stones, not just in Germany, but across Europe, remembering victims of the Nazis.

Stumbling stones are small brass plates placed at the last address where a person lived before they were deported or killed. Each stone reads “here lived” followed by the person’s name and place of birth, and the date and place of deportation or death, if known.

Mueller explained that “they are very subtle because they don't announce themselves. You can literally stumble over them, or you just see them and think, ‘what is that?’”

This makes them “a powerful reminder of how each neighborhood is affected by the deportation of fellow neighbors, friends, colleagues, family members.”

New stumbling stones are regularly added. Ordinary people, who might live in the house or be related to the person being remembered, take on the responsibility of researching what happened to the former residents who had been deported. They can then apply with that documentation and as much information as they are able to find out. The stones are handcrafted and, once they are ready, put in place.

The artist also published cleaning instructions so the inhabitants of the house know how to clean the brass and make it shine again, to honor those we remember and make the writing visible for everyone to read.

It makes sense to link to the Museum for the English articles. Just want to confirm that the Persian article will link to the IranWire translated material on IranWire's site.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments